September 8, 1941, began the Siege of Leningrad. The Nazi invaders sought to wipe the city off the face of the Earth and exterminate its inhabitants. The winter of 1942 itself proved that the pace of evacuation was to be stepped up. Every Leningrader was determined that the nation would stand up to the war. But at what

cost..?

The article is dedicated to the 100th Anniversary of Toktogon Altybasarova, a woman who

has become a symbol of goodness and mercy.

cost..?

The article is dedicated to the 100th Anniversary of Toktogon Altybasarova, a woman who

has become a symbol of goodness and mercy.

“THERE IS ALWAYS ROOM FOR HEROIC DEEDS”

In 2012, the capital of the Kyrgyz Republic, Bishkek, hosted the grand ceremony of unveiling the Siege of Leningrad Memorial, commemorating the people of the Kyrgyz SSR who sheltered the evacuated Leningraders during the Great Patriotic War. The black rectangular stele features the spire of the Peter and Paul Cathedral, caught in the searchlights over the Neva River, and just below it is a white marble bas-relief bearing a Kyrgyz woman cradling a Russian child.

Few people know that the Memorial rests on a capsule with soil from the Piskaryovskoye Memorial Cemetery, a mournful reminder of the genocide’s victims. The prototype of the Bishkek Memorial was Toktogon Altybasarova, a woman who became a legend by bestowing her truly maternal love on many children forced to flee the besieged Leningrad during the harsh years of war. As the sculptors conceived, the Memorial is meant to symbolise the spiritual bond between the peoples, strengthened during the Great Patriotic War, the struggle between the good and the evil, invaded with joy and engulfed in grief — all that those 872 days of the Siege are remembered for, — and also to commemorate the fate of the children who by chance found their home in the great space of the country.

“To the courage of the Leningraders and the nobility of the Kyrgyz” reads the short line on the Memorial to remind once again of the feat of arms of our peoples. The Union Republics of Central Asia provided a second home for tens of thousands of children. Something one can’t imagine nowadays, but back in the day, more than eight decades ago, hundreds of children left for the other end of the country with no par-ents and in almost complete obscurity. If only to survive, if only to have a chance to survive...

In 2012, the capital of the Kyrgyz Republic, Bishkek, hosted the grand ceremony of unveiling the Siege of Leningrad Memorial, commemorating the people of the Kyrgyz SSR who sheltered the evacuated Leningraders during the Great Patriotic War. The black rectangular stele features the spire of the Peter and Paul Cathedral, caught in the searchlights over the Neva River, and just below it is a white marble bas-relief bearing a Kyrgyz woman cradling a Russian child.

Few people know that the Memorial rests on a capsule with soil from the Piskaryovskoye Memorial Cemetery, a mournful reminder of the genocide’s victims. The prototype of the Bishkek Memorial was Toktogon Altybasarova, a woman who became a legend by bestowing her truly maternal love on many children forced to flee the besieged Leningrad during the harsh years of war. As the sculptors conceived, the Memorial is meant to symbolise the spiritual bond between the peoples, strengthened during the Great Patriotic War, the struggle between the good and the evil, invaded with joy and engulfed in grief — all that those 872 days of the Siege are remembered for, — and also to commemorate the fate of the children who by chance found their home in the great space of the country.

“To the courage of the Leningraders and the nobility of the Kyrgyz” reads the short line on the Memorial to remind once again of the feat of arms of our peoples. The Union Republics of Central Asia provided a second home for tens of thousands of children. Something one can’t imagine nowadays, but back in the day, more than eight decades ago, hundreds of children left for the other end of the country with no par-ents and in almost complete obscurity. If only to survive, if only to have a chance to survive...

YOUNG TOKTOGON

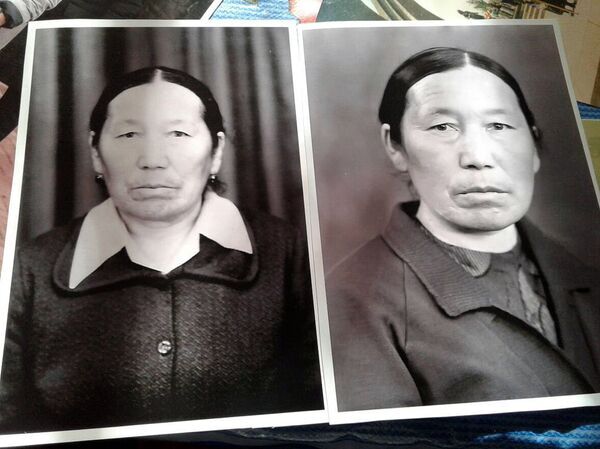

Toktogon Altybasarova was born in 1924, a tough year for the Turkestan ASSR. Hardly had the mutinous days of two revolutions thundered, the land of nomads still kept in memory the cattle losses, grief and pain endured by every inhabitant. And ahead loomed a war that would sweep the world and claim millions of lives...

But she, a little girl, came to know what the pain of loss was way before her peers. At the age of two she lost her father, and a little later her mother, who was taken by a long illness. Perhaps it was these events that shaped her mindset, nurtured a sense of how fragile human life is and, hence, worthy of being cherished.

“Losing a parent in childhood means growing up early,” said Marat Musayevich, her 62-year-old son, convinced, “she was left to take care of the younger ones — managed the house-hold, brought up two little sisters and a brother, assumed responsibility for their life. She had not yet started school, but already knew that their well-being would depend on her”.

Left a complete orphan, she was destined to rise early to the head of the social life of her native village. In her early childhood, she taught herself to read, and by listening to the radio, picked up Russian and later mastered Arabic. From all around the region, people turned to her as a translator, bringing letters and documents in both Russian and Arabic. Her phenomenal memory was a legend. She was sometimes reverentially called a “mine of information.”

Toktogon Altybasarova was 16 when the war unleashed. She graduated from school with honours and received a commendation in the name of Stalin, for which she was granted the right to assume the position of secretary of the local Komsomol and then the village council chairman.

And somewhere out there, miles away from her village, the sky was ripped by shelling, the enemy bombed Soviet cities, and the Red Army fought in the trenches with Wehrmacht soldiers. The Great Patriotic War echoed to the shores of Issyk-Kul. It was merely an echo of the war, but one that would soon unfold here, in front of their own eyes.

Toktogon Altybasarova was born in 1924, a tough year for the Turkestan ASSR. Hardly had the mutinous days of two revolutions thundered, the land of nomads still kept in memory the cattle losses, grief and pain endured by every inhabitant. And ahead loomed a war that would sweep the world and claim millions of lives...

But she, a little girl, came to know what the pain of loss was way before her peers. At the age of two she lost her father, and a little later her mother, who was taken by a long illness. Perhaps it was these events that shaped her mindset, nurtured a sense of how fragile human life is and, hence, worthy of being cherished.

“Losing a parent in childhood means growing up early,” said Marat Musayevich, her 62-year-old son, convinced, “she was left to take care of the younger ones — managed the house-hold, brought up two little sisters and a brother, assumed responsibility for their life. She had not yet started school, but already knew that their well-being would depend on her”.

Left a complete orphan, she was destined to rise early to the head of the social life of her native village. In her early childhood, she taught herself to read, and by listening to the radio, picked up Russian and later mastered Arabic. From all around the region, people turned to her as a translator, bringing letters and documents in both Russian and Arabic. Her phenomenal memory was a legend. She was sometimes reverentially called a “mine of information.”

Toktogon Altybasarova was 16 when the war unleashed. She graduated from school with honours and received a commendation in the name of Stalin, for which she was granted the right to assume the position of secretary of the local Komsomol and then the village council chairman.

And somewhere out there, miles away from her village, the sky was ripped by shelling, the enemy bombed Soviet cities, and the Red Army fought in the trenches with Wehrmacht soldiers. The Great Patriotic War echoed to the shores of Issyk-Kul. It was merely an echo of the war, but one that would soon unfold here, in front of their own eyes.

WHAT UNFOLDED STRUCK WITH HORROR

End of summer, a picturesque time in the Tian Shan foothills, the dull village of Kurmenty (Tüp, Issyk-Kul) seems to have grown dim and faded in the shadow of the great peaks of Küngöy Ala-Too and Terskey Alatoo Ranges...

Who would have thought that the last days of the summer of 1942 would forever change the his-tory of these places. Tidings came from Leningrad: “Children are coming.”

The villagers were ready for anything, but not for what awaited them.... “On 27 August they came by barge,” goes Marat Abdiyev’s story, “the village arranged for ten carts, filled with hay to ease the journey for the exhausted poor ones, and set off to meet the children, miraculously rescued across Ladoga from besieged Leningrad. Mummy recalled that it was scary to just look at them — skinny skeletons, terrified, starving, more dead than alive, with bloated tummies. Saucer eyes, displaying no hope, no light... Many were so feeble that could not even walk. These children were carried in the arms. The youngest were no more than two years old.”

Having crossed over 3000 kilometres, 150 children from besieged Leningrad had no clue (and were far from having a glimpse of one) that in their faraway homeland the railway connection — the last land corridor connecting the city to the country — was interrupt-ed a year ago. But they managed...

Children travelled from station to station in closed freight wagons, modified to carry passengers, under constant enemy fire, crossing the country by all means: first to Tuapse, then to Gagra, and then to Baku. In to-tal they covered twelve big cities and settlements. Tbilisi, Baku, Krasno-vodsk (Turkmenbashi), Tashkent and Frunze (Bishkek) were left behind, but it was not until almost three months of arduous journey that they reached the village of Kurmenty...

The children were to live in their new home for many years to come. Could they possibly have imagined it back then? Hardly... All they wanted was food, heat and security. And they got it.

The young Komsomol girl met the children along with the doctors and took the young ones, exhausted and dying, in her arms. What documents? What information? The first duty was to feed them, the second — to accommodate, and the third — to figure out what to do next. Doctors determined the age of the children by eye, and Toktogon gave them new names and surnames, as the cloth tags on their hands had faded from the tears shed over the long journey.

And each one had to be issued a birth certificate. We can only speculate on the effort it took to keep her poise under these circumstances. Toktogon did not just take care of them, but at her 17 she managed to convey all her love, maternal care and warmth. The children remembered how she sang lullabies, treated to real dainties — baked pumpkin slices that “tasted better than all the cakes in the world.” With time, they began to call her “Mummy Tonya.”

“Mummy never complained of that time, even though we often asked her about it. She only said that she felt very sorry for the children, that it was not their fault. When trouble comes, don’t stand aside, that’s what she taught us,” shares Marat Abdiyev. The children were accommodated in a hut-type house. The Kyrgyz people have an ancient tradition called Ashar, when people work together.

The children’s home was set up by the whole community. Having no utensils, not even mattresses, they stuffed bags with dry hay, and until the children’s home was put on state funding, every villager brought something from their own provisions daily — milk, fermented mare’s milk kumiss, sour-milk product qurut, vegetables — sometimes the last of what they had. They gave clothing, and those who could shared toys. Once the cold weather reined in, they knitted socks and sewed padded jackets out of felt. Meanwhile, the local woodworker carved figures of animals and birds as gifts for children from Leningrad. Knowing how hard life was for her fellow villagers, Toktogon asked nothing from them. Yet she spoke of the children in such a way that no one could remain indifferent.

Following Toktogon’s example, several other families also took in children — not at the behest of authority, but answering the call of the heart. Looking at the hungry children left without parents, Toktogon would often burst out into the street from the crushing walls, crying out of help-lessness and injustice... Giving vent to her feelings, she then dried her tears and returned to feed the children — 2-3 spoonfuls of milk per hour, as prolonged starvation allowed no more. Long days, weeks, and months passed, and her dedication bore fruit.

“The children began to recover and, as Mummy said, they started asking questions... Terrifying questions... Where am I? Where is my mom? What could she answer then... Hearing these questions, she couldn’t hold back her tears, having to respond that returning to Leningrad was not possible yet, that there was a war ravaging and they needed to gather strength. The older ones, of course, understood everything, but that didn’t make it any easier for them. Some shut off themselves from the world, nervous breakdowns were no exception.”

End of summer, a picturesque time in the Tian Shan foothills, the dull village of Kurmenty (Tüp, Issyk-Kul) seems to have grown dim and faded in the shadow of the great peaks of Küngöy Ala-Too and Terskey Alatoo Ranges...

Who would have thought that the last days of the summer of 1942 would forever change the his-tory of these places. Tidings came from Leningrad: “Children are coming.”

The villagers were ready for anything, but not for what awaited them.... “On 27 August they came by barge,” goes Marat Abdiyev’s story, “the village arranged for ten carts, filled with hay to ease the journey for the exhausted poor ones, and set off to meet the children, miraculously rescued across Ladoga from besieged Leningrad. Mummy recalled that it was scary to just look at them — skinny skeletons, terrified, starving, more dead than alive, with bloated tummies. Saucer eyes, displaying no hope, no light... Many were so feeble that could not even walk. These children were carried in the arms. The youngest were no more than two years old.”

Having crossed over 3000 kilometres, 150 children from besieged Leningrad had no clue (and were far from having a glimpse of one) that in their faraway homeland the railway connection — the last land corridor connecting the city to the country — was interrupt-ed a year ago. But they managed...

Children travelled from station to station in closed freight wagons, modified to carry passengers, under constant enemy fire, crossing the country by all means: first to Tuapse, then to Gagra, and then to Baku. In to-tal they covered twelve big cities and settlements. Tbilisi, Baku, Krasno-vodsk (Turkmenbashi), Tashkent and Frunze (Bishkek) were left behind, but it was not until almost three months of arduous journey that they reached the village of Kurmenty...

The children were to live in their new home for many years to come. Could they possibly have imagined it back then? Hardly... All they wanted was food, heat and security. And they got it.

The young Komsomol girl met the children along with the doctors and took the young ones, exhausted and dying, in her arms. What documents? What information? The first duty was to feed them, the second — to accommodate, and the third — to figure out what to do next. Doctors determined the age of the children by eye, and Toktogon gave them new names and surnames, as the cloth tags on their hands had faded from the tears shed over the long journey.

And each one had to be issued a birth certificate. We can only speculate on the effort it took to keep her poise under these circumstances. Toktogon did not just take care of them, but at her 17 she managed to convey all her love, maternal care and warmth. The children remembered how she sang lullabies, treated to real dainties — baked pumpkin slices that “tasted better than all the cakes in the world.” With time, they began to call her “Mummy Tonya.”

“Mummy never complained of that time, even though we often asked her about it. She only said that she felt very sorry for the children, that it was not their fault. When trouble comes, don’t stand aside, that’s what she taught us,” shares Marat Abdiyev. The children were accommodated in a hut-type house. The Kyrgyz people have an ancient tradition called Ashar, when people work together.

The children’s home was set up by the whole community. Having no utensils, not even mattresses, they stuffed bags with dry hay, and until the children’s home was put on state funding, every villager brought something from their own provisions daily — milk, fermented mare’s milk kumiss, sour-milk product qurut, vegetables — sometimes the last of what they had. They gave clothing, and those who could shared toys. Once the cold weather reined in, they knitted socks and sewed padded jackets out of felt. Meanwhile, the local woodworker carved figures of animals and birds as gifts for children from Leningrad. Knowing how hard life was for her fellow villagers, Toktogon asked nothing from them. Yet she spoke of the children in such a way that no one could remain indifferent.

Following Toktogon’s example, several other families also took in children — not at the behest of authority, but answering the call of the heart. Looking at the hungry children left without parents, Toktogon would often burst out into the street from the crushing walls, crying out of help-lessness and injustice... Giving vent to her feelings, she then dried her tears and returned to feed the children — 2-3 spoonfuls of milk per hour, as prolonged starvation allowed no more. Long days, weeks, and months passed, and her dedication bore fruit.

“The children began to recover and, as Mummy said, they started asking questions... Terrifying questions... Where am I? Where is my mom? What could she answer then... Hearing these questions, she couldn’t hold back her tears, having to respond that returning to Leningrad was not possible yet, that there was a war ravaging and they needed to gather strength. The older ones, of course, understood everything, but that didn’t make it any easier for them. Some shut off themselves from the world, nervous breakdowns were no exception.”

AFTER¥WAR PERIOD

In late January 1944, the long-await-ed joyful tidings came: “The city of Leningrad has been completely freed of the enemy blockade.” The Kurmenty children’s home was officially closed in 1952. By that time, most of the children had already grown up: some were found by their relatives, some scattered across the country to continue their studies, while others stayed in Kyrgyzstan, received an education, and started families. Toktogon worked as the village council secretary of Kurmenty for 44 years, was elected as a deputy to the village and district workers’ councils for 23 consecutive terms, as a people’s assessor of the Tüp People’s Court in 1949, and from 1964 to 1969, she was a member of the board of the Supreme Court of the Kyrgyz SSR. Until her last days, Toktogon Altybasarova did not forget her pupils, cared for them, sent letters and parcels, and remembered all her “fosterlings,” their illness-es, studies, and hobbies. Every autumn, Toktogon’s family sent apples and pears in plywood boxes to different ends of the country for her children. So, every year, her former students received a message from Kyrgyzstan, their second home during the war. Marat Abdiyev still keeps piles of letters that his mother received for over half a century from different regions of the former Soviet Union. Many of her children came to visit “Mummy Tonya.”

“The most precious to her were the letters from her children. They wrote after the war, and wrote a lot. She kept every letter, many of them survived. She often visit-ed Leningrad at the invitation of her grownup children. They never forgot each other. I’m sure that back in 1940s, they established a bond that neither time nor distance could destroy.

In late January 1944, the long-await-ed joyful tidings came: “The city of Leningrad has been completely freed of the enemy blockade.” The Kurmenty children’s home was officially closed in 1952. By that time, most of the children had already grown up: some were found by their relatives, some scattered across the country to continue their studies, while others stayed in Kyrgyzstan, received an education, and started families. Toktogon worked as the village council secretary of Kurmenty for 44 years, was elected as a deputy to the village and district workers’ councils for 23 consecutive terms, as a people’s assessor of the Tüp People’s Court in 1949, and from 1964 to 1969, she was a member of the board of the Supreme Court of the Kyrgyz SSR. Until her last days, Toktogon Altybasarova did not forget her pupils, cared for them, sent letters and parcels, and remembered all her “fosterlings,” their illness-es, studies, and hobbies. Every autumn, Toktogon’s family sent apples and pears in plywood boxes to different ends of the country for her children. So, every year, her former students received a message from Kyrgyzstan, their second home during the war. Marat Abdiyev still keeps piles of letters that his mother received for over half a century from different regions of the former Soviet Union. Many of her children came to visit “Mummy Tonya.”

“The most precious to her were the letters from her children. They wrote after the war, and wrote a lot. She kept every letter, many of them survived. She often visit-ed Leningrad at the invitation of her grownup children. They never forgot each other. I’m sure that back in 1940s, they established a bond that neither time nor distance could destroy.

MEMORY AND HISTORY

It is said that it does not matter how long you live, but how well you do it. On May 9, 2015, Russia and former Soviet Union countries marked the 70th Anniversary of the unconditional surrender of fascist Germany and the end of the Great Patriotic War. Toktogon Altybasarova was fortunate to live to see this memorable date; however, just a month later, a prolonged illness took her away. On June 11, 2015, the president of Kyrgyzstan sent a mourning letter to her relatives.

In March 2024, in honor of the 80th Anniversary of the complete liberation of Leningrad from the fascist blockade and in recognition of her significant contribution to the upbringing of children evacuated from the besieged city to the Kyrgyz SSR, by the decree of the president of the Kyrgyz Republic Sadyr Japarov, Toktogon Altybasarova was posthumously awarded the honorary title of Emgek Baatyry.

The year 2024 was declared by Russia’s President Vladimir Putin the Year of Family, with a program that is, not least, aimed at supporting humanitarian intergovernmental relations. As history shows, motherhood, caring for children and parents, a sense of responsibility for loved ones have remained common for the peoples of Kyrgyzstan and Russia for many centuries.

In this regard, it seems perfectly logical that today the Family Education Support Center No. 4 (Yaroslavsky Prospekt, St. Petersburg) is named after Toktogon Altynbasarova.

It is said that it does not matter how long you live, but how well you do it. On May 9, 2015, Russia and former Soviet Union countries marked the 70th Anniversary of the unconditional surrender of fascist Germany and the end of the Great Patriotic War. Toktogon Altybasarova was fortunate to live to see this memorable date; however, just a month later, a prolonged illness took her away. On June 11, 2015, the president of Kyrgyzstan sent a mourning letter to her relatives.

In March 2024, in honor of the 80th Anniversary of the complete liberation of Leningrad from the fascist blockade and in recognition of her significant contribution to the upbringing of children evacuated from the besieged city to the Kyrgyz SSR, by the decree of the president of the Kyrgyz Republic Sadyr Japarov, Toktogon Altybasarova was posthumously awarded the honorary title of Emgek Baatyry.

The year 2024 was declared by Russia’s President Vladimir Putin the Year of Family, with a program that is, not least, aimed at supporting humanitarian intergovernmental relations. As history shows, motherhood, caring for children and parents, a sense of responsibility for loved ones have remained common for the peoples of Kyrgyzstan and Russia for many centuries.

In this regard, it seems perfectly logical that today the Family Education Support Center No. 4 (Yaroslavsky Prospekt, St. Petersburg) is named after Toktogon Altynbasarova.

BEST TRADITIONS

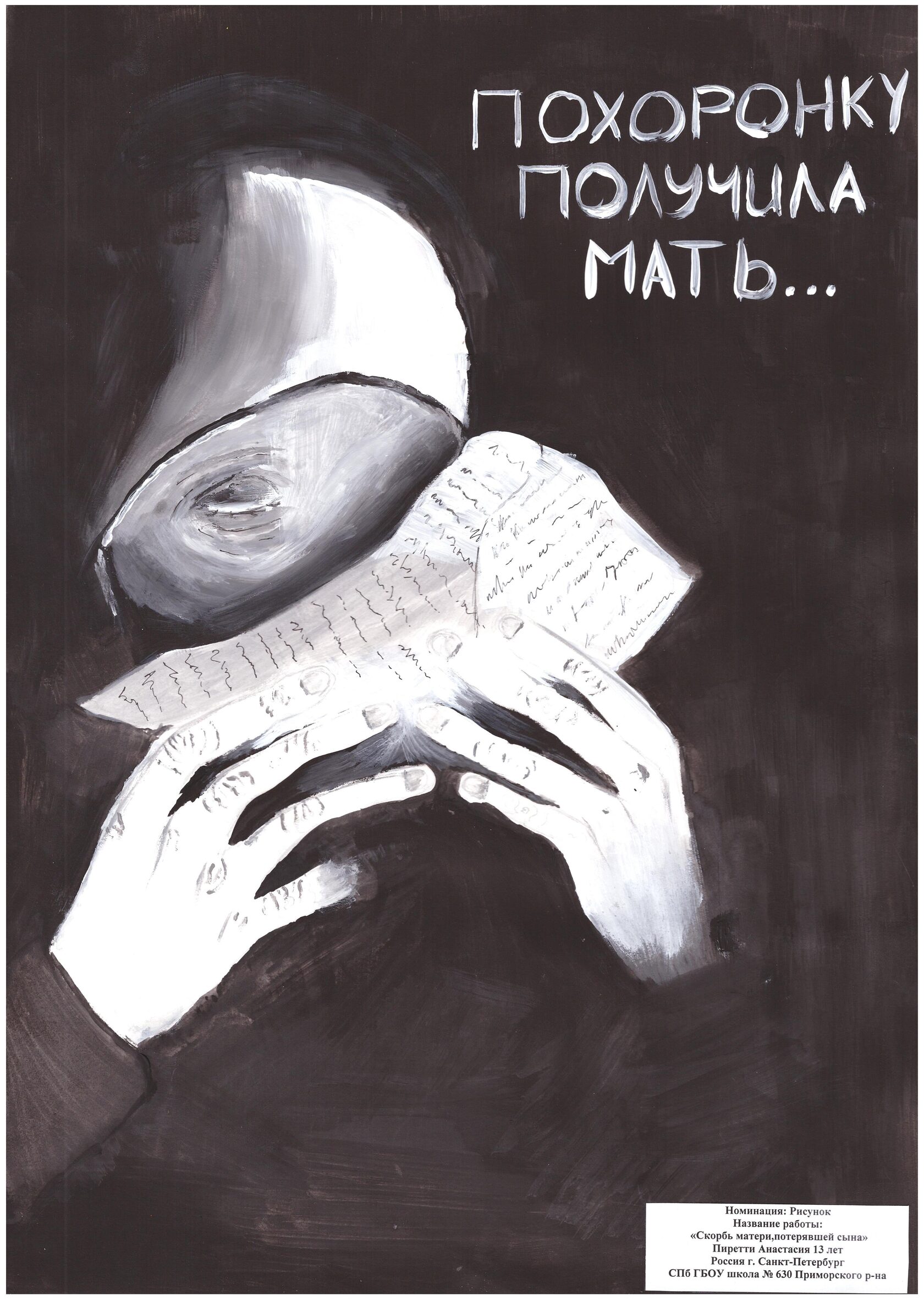

The dialogue between people still remains a good means of supporting benevolent and constructive endeav-ours — a view shared by the Union of Women for Traditional Values. It was this public organisation that put forth the initiative to hold the international forum “Motherhood. Mercy. Memory” in 2024, which brought together Kyrgyzstan, Belarus, Georgia, Israel, Russia, Uzbekistan, France, as well as religious denominations and public organisations. In anticipation of the Forum, an international competition of drawings, photographs, and essays devoted to the same theme took place, aimed at preserving and strengthening historical memory of the youth, promoting moral values of society, the family as the fundamental unit of society, patriotism, humanism, and interethnic harmony. The key event of the forum “Motherhood. Mercy. Memory” was the unveiling of the Memorial to Toktogon Altybasarova and the Alley of Mothers, featuring nameplates of Altybasarova’s fellow villagers who became symbols of mercy.

These women, who once took children from besieged Leningrad into their families and found place for them in their hearts, giving them a normal life and protection, are now forever engraved in stone and bronze. The ceremony took place on June 9, 2024, in the village of Ak-Bulung (Bright Cape) in Tüp (Issyk-Kul, Kyrgyzstan). The Minister of Defense of the Kyrgyz Republic, Lieutenant General Baktybek Bekbolotov, the Military Attaché at the Russian Embassy,

Colonel Igor Dovbnya, and the First Deputy Plenipotentiary Representative of the President of the Kyrgyz Republic in Issyk-Kul Region, Daniyar Arpachiev, solemnly unveiled the Memorial, paying tribute to the maternal feat.

On that day, the band playing a martial air, the mounted guard of honour, the laid wreaths, and words of gratitude tied the past and the present... The Memorial, created by the renowned sculptor of the republic Ulan Sadykov and erected by the children of the Meerim Bulagy children’s home under the initiative of its director Gulnara Degenbaeva, serves as an eternal reminder of the boundless strength of maternal love. It is a stone arch slab against which stands a miniature woman embraced by exhausted children. The very same place, on the initiative of Bishop Savva of Kyrgyzstan and Bishkek and the Union of Women for Traditional Values, became the venue for the opening ceremony of the Eurasian platform for family up-bringing “People’s Spiritual and Educational Center of Mother and Mercy” named after Toktogon Altybasarova.

The events of the forum “Motherhood. Mercy. Memory” were organised in collaboration with the Bishkek and Kyrgyzstan diocese, the Kyrgyz Society of Leningrad Siege Survivors, the Toktogon Altybasarova Foundation, Meerim Bulagy private children’s home, and with the support of the Embassy of the Russian Federation, the Russian House in Bishkek, the Ministry of Defense of the Kyrgyz Republic, the Ministry of Culture, In-formation, Sports and Youth Policy of the Kyrgyz Republic, the Kyrgyzfilm National Film Studio named after T. Okeyev, the Archival Service under the Ministry of Digital Development of the Kyrgyz Republic, the Issyk-Kul Regional Administration, and the Tüp District State Administration.

The Forum was also prepared with the support of Gazprom Kyrgyzstan, the Sokolov Dental Clinic, the Boundless Love public charity foundation, the MEDUZA design studio, the LinkKG computer equipment store, and the Kulikovsky confectionery house. The Forum culminated in a sol-emn evening dedicated to the feat of the people of Kyrgyzstan during the Great Patriotic War, which took place at the Sadylganov State Philharmonic Hall.

The music and poems performed touched the heart of every viewer. With tears in their eyes, they listened to stories about the horrors of the Great Patriotic War, the children of the besieged Leningrad, and the feat of mercy of all the Kyrgyz people, who were in the rear and contributed to the common Victory.

And Toktogon Altybasarova was not the only woman, who took on the role of a mother — about 800 children, left without parents, were taken in by Kyrgyz families. Soviet people made no difference between their own children and fosterlings. However, the feat of Toktogon was indeed unprecedented, she became an embodiment of infinite humanity and goodness, compassion, and motherhood.

The dialogue between people still remains a good means of supporting benevolent and constructive endeav-ours — a view shared by the Union of Women for Traditional Values. It was this public organisation that put forth the initiative to hold the international forum “Motherhood. Mercy. Memory” in 2024, which brought together Kyrgyzstan, Belarus, Georgia, Israel, Russia, Uzbekistan, France, as well as religious denominations and public organisations. In anticipation of the Forum, an international competition of drawings, photographs, and essays devoted to the same theme took place, aimed at preserving and strengthening historical memory of the youth, promoting moral values of society, the family as the fundamental unit of society, patriotism, humanism, and interethnic harmony. The key event of the forum “Motherhood. Mercy. Memory” was the unveiling of the Memorial to Toktogon Altybasarova and the Alley of Mothers, featuring nameplates of Altybasarova’s fellow villagers who became symbols of mercy.

These women, who once took children from besieged Leningrad into their families and found place for them in their hearts, giving them a normal life and protection, are now forever engraved in stone and bronze. The ceremony took place on June 9, 2024, in the village of Ak-Bulung (Bright Cape) in Tüp (Issyk-Kul, Kyrgyzstan). The Minister of Defense of the Kyrgyz Republic, Lieutenant General Baktybek Bekbolotov, the Military Attaché at the Russian Embassy,

Colonel Igor Dovbnya, and the First Deputy Plenipotentiary Representative of the President of the Kyrgyz Republic in Issyk-Kul Region, Daniyar Arpachiev, solemnly unveiled the Memorial, paying tribute to the maternal feat.

On that day, the band playing a martial air, the mounted guard of honour, the laid wreaths, and words of gratitude tied the past and the present... The Memorial, created by the renowned sculptor of the republic Ulan Sadykov and erected by the children of the Meerim Bulagy children’s home under the initiative of its director Gulnara Degenbaeva, serves as an eternal reminder of the boundless strength of maternal love. It is a stone arch slab against which stands a miniature woman embraced by exhausted children. The very same place, on the initiative of Bishop Savva of Kyrgyzstan and Bishkek and the Union of Women for Traditional Values, became the venue for the opening ceremony of the Eurasian platform for family up-bringing “People’s Spiritual and Educational Center of Mother and Mercy” named after Toktogon Altybasarova.

The events of the forum “Motherhood. Mercy. Memory” were organised in collaboration with the Bishkek and Kyrgyzstan diocese, the Kyrgyz Society of Leningrad Siege Survivors, the Toktogon Altybasarova Foundation, Meerim Bulagy private children’s home, and with the support of the Embassy of the Russian Federation, the Russian House in Bishkek, the Ministry of Defense of the Kyrgyz Republic, the Ministry of Culture, In-formation, Sports and Youth Policy of the Kyrgyz Republic, the Kyrgyzfilm National Film Studio named after T. Okeyev, the Archival Service under the Ministry of Digital Development of the Kyrgyz Republic, the Issyk-Kul Regional Administration, and the Tüp District State Administration.

The Forum was also prepared with the support of Gazprom Kyrgyzstan, the Sokolov Dental Clinic, the Boundless Love public charity foundation, the MEDUZA design studio, the LinkKG computer equipment store, and the Kulikovsky confectionery house. The Forum culminated in a sol-emn evening dedicated to the feat of the people of Kyrgyzstan during the Great Patriotic War, which took place at the Sadylganov State Philharmonic Hall.

The music and poems performed touched the heart of every viewer. With tears in their eyes, they listened to stories about the horrors of the Great Patriotic War, the children of the besieged Leningrad, and the feat of mercy of all the Kyrgyz people, who were in the rear and contributed to the common Victory.

And Toktogon Altybasarova was not the only woman, who took on the role of a mother — about 800 children, left without parents, were taken in by Kyrgyz families. Soviet people made no difference between their own children and fosterlings. However, the feat of Toktogon was indeed unprecedented, she became an embodiment of infinite humanity and goodness, compassion, and motherhood.

Photos and video provided by: Ministry of Defence of the Kyrgyz Republic, Bishkek and Kyrgyz Diocese, Archive Service underthe Ministry of Digital Development of the Kyrgyz Republic, Union of Women for Traditional Values, and M. Musaev, son of T. Altybasarova from the family’s private archive.

The editorial expresses gratitude to Elena Soklakova, co-founder and board member of the Union of Women

for Traditional Values (Kyrgyz Republic) for her assistance in preparing the article.

for Traditional Values (Kyrgyz Republic) for her assistance in preparing the article.